As a newly hired ethics instructor at the Stockdale Center, I think it somewhat appropriate at this moment in time to share some of my thoughts and reflections on the man whom this center is named after, his legacy, and my specific relationship to both.

In life, some people, some types of people, dare I say, some archetypal types of people, have a way of weaving their way in and out of your life, time and again, in some of the most profound and subtle ways; and it is only years later, after quiet and careful reflection, does one come to truly appreciate the magnitude and impact that that person’s life has had upon one’s own. Admiral James B. Stockdale has been one of those kinds of people for me.

Like many Americans, probably the majority of Americans, sadly, my first impression of Admiral Stockdale was during the 1992 presidential run-off when he served as running mate alongside third-party candidate, Ross Perot. After a handful of what were deemed sub-par media performances by the media elite, the mainstream media machine got to work eviscerating Admiral Stockdale’s public image and reputation, generating a slanderous media campaign and near-criminal misrepresentation of him as a confused old man, wholly unfit for leadership, and nothing more. The late-night television hosts reinforced this message, the pre-recorded laugh tracks reconfirmed it, and for my then 12-year-old mind, that seemed as good as gospel for me.

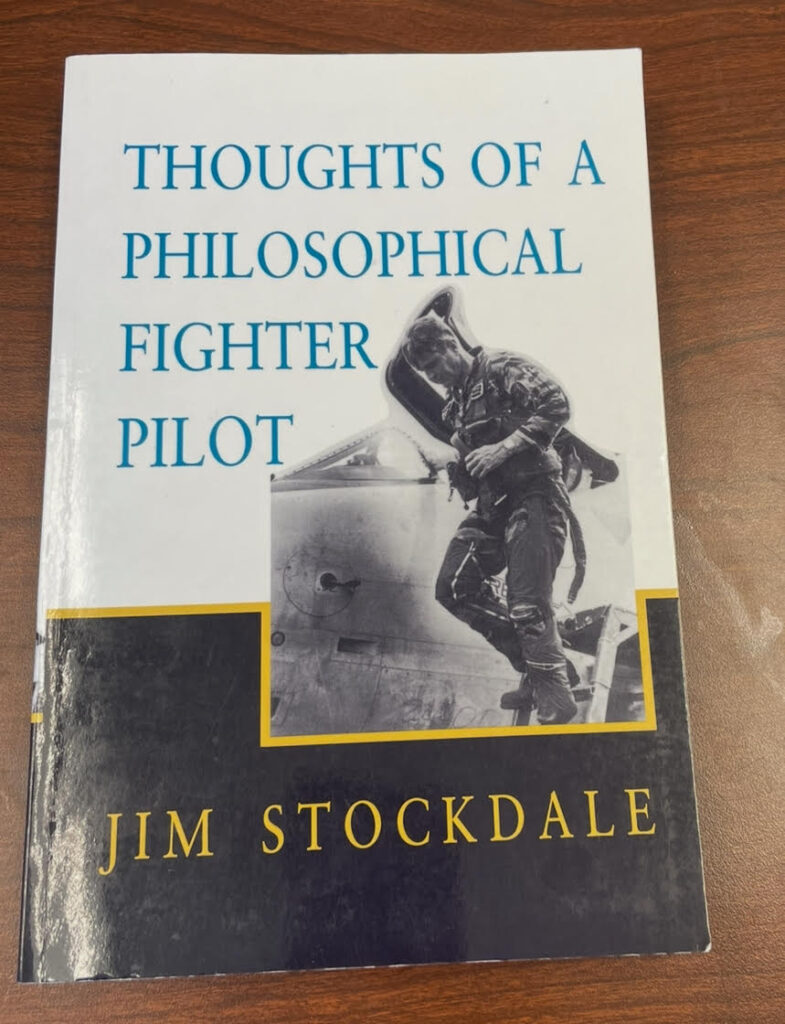

Several years later, however, during my plebe year at the United States Military Academy, in the West Point bookstore, I was re-introduced to a slightly different version of the man. Maybe it was the title; Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot. Maybe it was the font style. Or maybe it was the imagery on the front cover; a black and white photograph of a lone, Vietnam-era, American pilot, standing on the ladder of his Skyhawk, head slightly down, and displaying what appeared to be a reflective, contemplative, and almost gentle demeanour. Whatever it was, I felt compelled to pick the book up from off the shelf and to begin reading the back cover. This, of course, threw my mind into immediate disorientation, disbelief, and utter confusion.

“Written by 3-star Naval Admiral, Stanford-educated philosopher, Medal of Honor recipient… Jim… Stockdale???… Wait, that old guy who ran for vice president awhile back? That Stockdale?!”

The otherwise settled assumptions in my mind about this man and who he was had been suddenly and radically disrupted. I had to read more.

There, in those pages, as a 19-year-old cadet, I came to learn, for the very first time, all about the real James Stockdale; the Naval officer, the philosopher, the warrior, the prison-camp resistance leader, the husband, the father, the American patriot. Many of the specifics of the book have faded from memory, but certain highlights still stand out.

I remember him writing about his thoughts under canopy as he slowly drifted down from the sky after his fighter jet had just been shot down, contemplating the hardship, uncertainty, and existential gravity of what was soon to come next. I remember him writing about stepping up as senior officer in Hanoi to lead the American resistance effort within the camp. I remember his description of American POWs communicating secretly with one another via tap codes on the prison walls and by exchanging secret letters among one another written on tissue paper with rat droppings. I remember his detailed description of the brutal mechanics and visceral pain of the specific limb-stretching torture methods that the Vietnamese interrogators frequently employed on both him and his fellow American POWs. I remember him cleverly and courageously using a sitting stool to suddenly smash open his own face in order to pre-emptively spoil anticipated Vietnamese efforts to record him on film for future propaganda purposes. I remember attributing his fortitude and resolve during his time in Hanoi as the result of two main influences: his reading of the writings of the Stoic, Epictetus, and his plebe year at the U.S. Naval Academy. Lastly, I remember his radical prescription given during one of his commencement speeches; that contrary to the ethic of hyper-individualism so dominant and prevalent in mainstream American culture today, that despite all this, ‘you are your brother’s keeper’ and that we as Americans and members of the human race actually have duties to one another beyond just ourselves. These were some of the highlights that most stuck with me.

In 2001, Admiral Stockdale came to speak at West Point. I can’t remember a single word that the man said that night. What I do remember, however, were two distinct things; one, the limp in his left leg; the same leg that was shattered during his initial ejection when he was first shot down over Vietnam, the same leg that was denied medical attention by his captors, and then deliberately reinjured multiple times by his torturers during his time in Hanoi; and, two, the gravity in the air of the entire auditorium during the entire time that he spoke. I’m not sure if any of us young cadets followed the specifics and the nuances of what he said, but what we all felt, what we all understood, in our bones, was what this man stood for and what he represented, and that the words he shared seemed to not carry just knowledge, but wisdom; first-hand, hard-fought wisdom earned in the halls of the Naval Academy, in the Philosophy seminars at Stanford, in the skies of Vietnam, and in the crucible of Hanoi. We were all getting to witness something very special that night.

After the talk ended, we all walked back to the barracks, but then, on a complete whim and at the encouragement of a good friend, I got the idea to run back to the auditorium in hopes of meeting Admiral Stockdale in person and introducing myself. Sprinting back in my class-A uniform and low-quarters on the unforgiving cement and under minimal visibility, heels being shredded, I hoped to catch Admiral Stockdale and his entourage as they exited one of the many exits of Thayer Hall. However, by the time I got back, it looked like everyone had already left, and that I would not be getting to meet my hero face-to-face that night. What I would have actually said to him, I still have no idea.

After that night, the rhythm of the academy returned back to normal and life moved on as usual. I went on to dive deeper into Philosophy and to learn more, not just about Epictetus and the Stoics, but also about Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Kant, and about some of the other most influential philosophers and thinkers of Western and Eastern thought, both ancient and modern. I would commission in 2002, and soon find myself leaning on and drawing strength, motivation, and guidance from all of these ideas both in Ranger School and in the streets of Baghdad, Iraq with the 82nd Airborne Division the very next year.

I finished my active-duty service time in 2007 and decided to attempt to turn my passion for philosophy into a career. As I did so, however, I would come to discover that my connection to Admiral Stockdale’s legacy and influence was still not over yet. During grad school I would be invited to give a talk at the Stockdale Center in 2014. The following year, I would become a Class of 1964 Stockdale fellow for the year. And in both 2016 and 2019, I would speak on several panels at the Stockdale Center’s annual McCain conference.

Now, in 2025, as a newly hired ethics instructor at the Stockdale Center, I feel like things have come full circle. I started out picking up a random book at the cadet bookstore because of an interesting title and cover; a quarter-century later, I now find myself working at the center bearing that author’s namesake, surrounded by fellow travelers motivated and entrusted to keep Admiral Stockdale’s influence and legacy alive for the next generation of midshipmen and future naval officers. To say that I am honored would be an understatement.

A few weeks ago, I was manning the Stockdale Center table during Plebe Parent Weekend at USNA in order to pass out flyers for our ethics debate team. Most parents were understandably overloaded by the entire affair and probably didn’t even notice our table. Some took some of our flyers. And some parents even stopped to chat for a bit. One parent, in particular, however, radically stuck out in my mind. As he walked past our table, he stopped dead in his tracks, fixated on Admiral Stockdale’s autobiography that we had on display, the same book and image that caught my attention in the West Point bookstore all those years ago. Pausing for an exceptionally long and awkward silence, I notice that the man was fighting back tears. With his voice trembling, he eventually was able to get out “I know that man… I know who that man is.” In that moment, I struggled to hold back tears myself. He then went on to explain to me that he had met and actually interviewed several other Vietnam POW survivors from Hanoi himself as an amateur journalist and that he was well aware of James Stockdale, who he was, and what he represented. We chatted for a few more minutes about Admiral Stockdale, Vietnam, the Academy, and his plebe who was just finishing up basic training. As he departed, he said, solemnly, “Thank you all for my freedom.”

In the present zeitgeist, it seems now the increasing fashion to mock the heroes of our past, if not the very idea heroism itself; to highlight and exaggerate their human imperfections, to denigrate the institutions and traditions that they stood and fought for; and to portray such heroes as ultimately standing upon feet of clay, worthy of neither remembrance nor honoring at all. Indeed, the nihilistic anti-hero is somehow now the cool thing to ultimately aspire to it seems. I’m not at all sure where such a notion or sentiment fundamentally comes from. Perhaps it is jealousy. Perhaps it is resentment. Or perhaps it is human nature, the weaker part of our nature, to seek to level the playing field a bit; to downplay the character, actions, and accomplishments of such giants in order to make them feel a bit smaller, a bit weaker, and to thereby make our own inadequacies, moral failings, and wasted potential feel that much less pronounced. I’m not sure what it is exactly, but I do know one thing; that no institution, military, nation, or civilization can survive for very long with its people maintaining such an attitude and such a posture of the soul. In a world of increased division, of us versus them, of left versus right, or this camp versus that camp, and so on, Admiral Stockdale, I believe, represents to us, what Epictetus ultimately represented to him way, back in the dark and unforgiving prisons of Hanoi; that is, in times of hardship and in times of crisis, someone to look up to. May we all keep looking up.

1 I credit Brad Snyder with this poignant observation about the rise of the ‘anti-hero’ in present American culture.